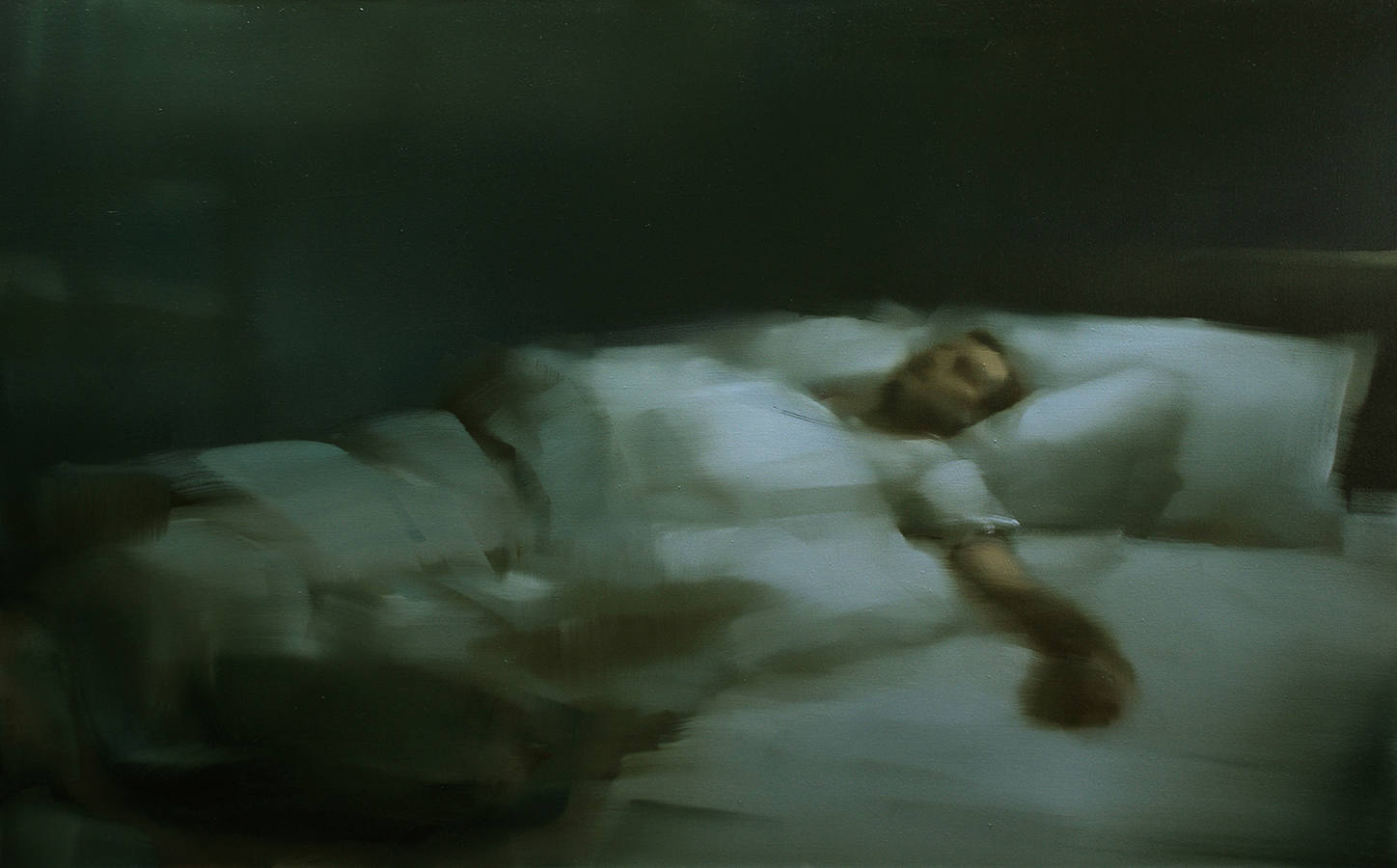

One of the works shows a man sprawled on a bed with his left arm extended towards the viewer. The broad sketchy brushstrokes veil his features and make it impossible to tell whether he is even alive or simply resting in a state of post-coital oblivion. Herein the work suggests that the difference between death and ‘the little death’ is as negligible as the coined phrase would have it.

The ever-present narrative in Heiska’s work seems heightened in her most recent work, which is a continuation of her 2005 ‘Hotel’ series. The enhanced narrative owes partly to the fact that the work is inspired by moving images, specifically Buñuel’s iconic Belle de Jour, as opposed to her photography-based earlier work. In this series, certain areas are depicted like superimposed images that generate an almost stroboscopic effect, which the viewer then perceives as motion. In her work, Heiska employs this photographic multiple exposure technique to create the ghost-like effect that her characterizes her paintings.

As in Heiska’s earlier work, all of the canvases are varnished giving them a sensuous light-reflecting surface reminiscent of historical artworks. To the viewer, the shiny surface produces a sensation of seeing something through glass and it retains the eerie features of a one-way-mirror, as the characters on the other side of the glass are as unable to return the gaze as they are unaware of being watched. Smooth as mirrors, the painting echo the silver screen but in a way that allows us see ourselves seeing, i.e. makes us highly aware of our sensory perception and thus of our role as viewers.

A leitmotif in Heiska’s artistic production is the sense that everything is veiled in imminent danger. Even the most innocently looking scene has a backdoor ajar into the unexplored depths and depravities of the human mind. By merely suggesting a lurking threat or a situation gone terribly wrong, the artist shrouds the tableau in a mantle of mystery.

In one painting, a man and a woman are lying on a bed in what appears to be a broken-off embrace. The direction and movement of the woman’s naked legs indicate that she is resisting the man’s efforts to undress her, and it would seem as if she is trying to escape. Due to the degree of abstraction, the figures remain in a constant state of merging and separating, and it consequently remains unclear whether the woman is resisting or giving in. A similar ambiguity can be found in Buñuel’s Belle de Jour, where the female protagonist is torn between her fantasies of sexual exploitation and her role as a faithful loving wife.

As such, Heiska’s work keeps appearing and dissolving in front of us like a watermark or a half forgotten memory enticing us to lose ourselves in the boundless shadowlands of release.

Maria Bregnbak, Art Historian, DK