Gallery Ama 10.9.2021–3.10.2021

Press Release

“When I was 12, I fell in love with Catherine Deneuve in the film The Umbrellas of Cherbourg, which I went to see with my mother and grandmother. I thought her face was breathtakingly beautiful, unapproachable, as if there were a space around her where the air is so thin that no one else can breathe it. In my eyes she had the same sad gaze as my grandmother, who I idolized,” Tiina Heiska says.

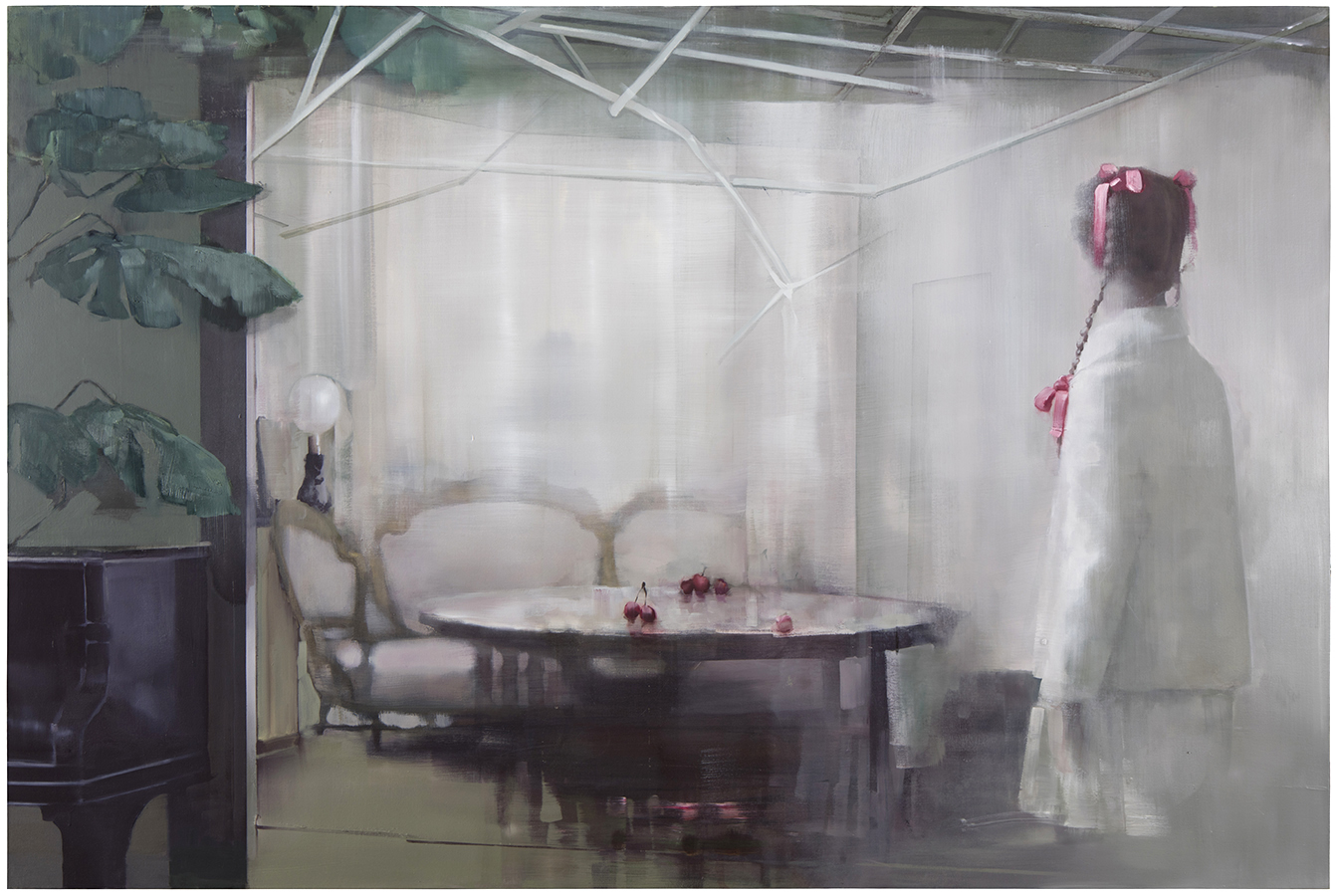

Heiska’s grandmother was a former small-town beauty queen. The higher standard of living afforded by her grandfather’s increasing prosperity led to her grandmother giving up the job as a hairdresser that she loved and staying in her beautiful home to tend her beauty, which faded from day to day. In Luis Buñuel’s film Belle de Jour Deneuve plays the coolly ethereal, bored housewife, Séverine, who beneath her closed outer shell gives in to the sadomasochistic daydreams that obsessively drive her, and ultimately lives out her fantasies by secretly working in a brothel. “Like Séverine, my grandmother kept up the impeccable appearances of petty-bourgeois life, but I don’t know what went on under the surface, what she dreamed of doing, what her fantasies were,” Heiska muses, as she replaces her unapproachable grandmother in her paintings with the figure of Séverine.

“In practice I am someone who has been shaped by books and films. They are the gaze that looks at me and defines me,” writes Anu Silfverberg in Sinut on nähty [You Have Been Seen]. “The same could be said of myself,” Heiska says. What is going on in that gaze? In the 1970s, one of the pioneers of feminist film theory, Laura Mulvey, developed a theory based on Lacanian psychoanalysis, which sought to explain the subordinate status of the female characters in mainstream western film. According to Mulvey, in film imagery, women are situated through three gazes: those of the characters, of the camera, and of the viewer of the film. Who is looking and who they are looking at are used to define which object of the gaze is desirable and who has the right to desire.

The scene in the film when Séverine accidentally drops a bottle of perfume on the bathroom floor is intercut with a flashback from her childhood, in which a man in grubby workman’s clothes molests her. Is that what we are offered as a key to Séverine’s fantasies? Are we to interpret them as a symptom of a traumatic experience?

Heiska offers another interpretation: “Séverine is initially like a puppet in her own life, a puppet who is looked at and who does what has been programmed into her role. What if this is ultimately about her own rage against that puppet? That is to say, when Séverine finally takes action and gets a job in a brothel so as to live out her daydreams, her transformation from object of the gaze to viewer begins.”

In his essay Glances of Desire Marvin D’Lugo writes about the scene in which Séverine watches a masochistic session through a spyhole in the brothel wall, she realizes that what she is seeing is a mirror image of herself. So, now, Séverine is able to enjoy her own “emancipated” gaze, and with that to experience being in charge of her own pleasure when she surrenders to her clients’ wishes and to being the object of the young man Marcel’s passion. In the end her husband is blinded, shot by Marcel, and thus the male gaze is eliminated entirely. Severine alone controls the gaze. Object and subject swap places. Severine says that, since her husband’s accident, her dreams have stopped. “Strange. Since your… accident, I’ve had no more nightmares.”

Further information, gallery@ama.email or https://www.ama.fi